Deforestation: development of road infrastructure

Deforestation

Deforestation, clearance, clearcutting, or clearing is the removal of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use.[3] Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. The most concentrated deforestation occurs in tropical rainforests.[4] About 31% of Earth's land surface is covered by forests.[5] Between 15 million to 18 million hectares of forest, an area the size of Belgium, are destroyed every year, on average 2,400 trees are cut down each minute.[6]

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations defines deforestation as the conversion of forest to other land uses (regardless of whether it is human-induced). "Deforestation" and "forest area net change" are not the same: the latter is the sum of all forest losses (deforestation) and all forest gains (forest expansion) in a given period. Net change, therefore, can be positive or negative, depending on whether gains exceed losses, or vice versa.[7]

For instance, FAO estimate that the global forest carbon stock has decreased 0.9%, and tree cover 4.2% between 1990 and 2020.[8] The forest carbon stock in Europe (including Russia) increased from 158.7 to 172.4 Gt between 1990 and 2020. In North America, the forest carbon stock increased from 136.6 to 140 Gt in the same period. However, carbon stock decreased from 94.3 to 80.9 Gt in Africa, 45.8 to 41.5 Gt in South and Southeast Asia combined, 33.4 to 33.1 Gt in Oceania, 5 to 4.1 Gt in Central America, and from 161.8 to 144.8 Gt in South America.[9] The IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) states that there is disagreement about whether the global forest is shrinking or not, and quote research indicating that tree cover has increased 7.1% between 1982 and 2016.[a] IPCC also writes: «While above-ground biomass carbon stocks are estimated to be declining in the tropics, they are increasing globally due to increasing stocks in temperate and boreal forests […].»[10]

Agricultural expansion continues to be the main driver of deforestation and forest fragmentation and the associated loss of forest biodiversity.[11] Large-scale commercial agriculture (primarily cattle ranching and cultivation of soya bean and oil palm) accounted for 40 percent of tropical deforestation between 2000 and 2010, and local subsistence agriculture for another 33 percent.[11] Trees are cut down for use as building material, timber or sold as fuel (sometimes in the form of charcoal or timber), while cleared land is used as pasture for livestock and agricultural crops. The vast majority of agricultural activity resulting in deforestation is subsidized by government tax revenue.[12] Disregard of ascribed value, lax forest management, and deficient environmental laws are some of the factors that lead to large-scale deforestation. Deforestation in many countries—both naturally occurring[13] and human-induced—is an ongoing issue.[14] Between 2000 and 2012, 2.3 million square kilometres (890,000 sq mi) of forests around the world were cut down.[15] Deforestation and forest degradation continue to take place at alarming rates, which contributes significantly to the ongoing loss of biodiversity.[11]

The removal of trees without sufficient reforestation has resulted in habitat damage, biodiversity loss, and aridity. Deforestation causes extinction, changes to climatic conditions, desertification, and displacement of populations, as observed by current conditions and in the past through the fossil record.[17] Deforestation also has adverse impacts on biosequestration of atmospheric carbon dioxide, increasing negative feedback cycles contributing to global warming. Global warming also puts increased pressure on communities who seek food security by clearing forests for agricultural use and reducing arable land more generally. Deforested regions typically incur significant other environmental effects such as adverse soil erosion and degradation into wasteland.

The resilience of human food systems and their capacity to adapt to future change depends on that very biodiversity – including dryland-adapted shrub and tree species that help combat desertification, forest-dwelling insects, bats and bird species that pollinate crops, trees with extensive root systems in mountain ecosystems that prevent soil erosion, and mangrove species that provide resilience against flooding in coastal areas.[11] With climate change exacerbating the risks to food systems, the role of forests in capturing and storing carbon and mitigating climate change is of ever-increasing importance for the agricultural sector.[11]

According to a study published in Scientific Reports if deforestation continue in current rate in the next 20 – 40 years, it can trigger a full or almost full extinction of humanity. To avoid it humanity should pass from a civilization dominated by the economy to "cultural society" that "privileges the interest of the ecosystem above the individual interest of its components, but eventually in accordance with the overall communal interest"[18]

Deforestation is more extreme in tropical and subtropical forests in emerging economies. More than half of all plant and land animal species in the world live in tropical forests.[19] As a result of deforestation, only 6.2 million square kilometres (2.4 million square miles) remain of the original 16 million square kilometres (6 million square miles) of tropical rainforest that formerly covered the Earth.[15] An area the size of a football pitch is cleared from the Amazon rainforest every minute, with 136 million acres (55 million hectares) of rainforest cleared for animal agriculture overall.[20] More than 3.6 million hectares of virgin tropical forest was lost in 2018.[21] Consumption and production of beef is the primary driver of deforestation in the Amazon, with around 80% of all converted land being used to rear cattle.[22][23] 91% of Amazon land deforested since 1970 has been converted to cattle ranching.[24][25] The global annual net loss of trees is estimated to be approximately 10 billion.[26][27] According to the Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020 the global average annual deforested land in the 2015–2020 demi-decade was 10 million hectares and the average annual forest area net loss in the 2000–2010 decade was 4.7 million hectares.[7] The world has lost 178 million ha of forest since 1990, which is an area about the size of Libya.[7

Causes

According to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) secretariat, the overwhelming direct cause of deforestation is agriculture. Subsistence farming is responsible for 48% of deforestation; commercial agriculture is responsible for 32%; logging is responsible for 14%, and fuel wood removals make up 5%.[28]

Experts do not agree on whether industrial logging is an important contributor to global deforestation.[29][30] Some argue that poor people are more likely to clear forest because they have no alternatives, others that the poor lack the ability to pay for the materials and labour needed to clear forest.[29] One study found that population increases due to high fertility rates were a primary driver of tropical deforestation in only 8% of cases.[31]

Other causes of contemporary deforestation may include corruption of government institutions,[32][33] the inequitable distribution of wealth and power,[34] population growth[35] and overpopulation,[36][37] and urbanization.[38] Globalization is often viewed as another root cause of deforestation,[39][40] though there are cases in which the impacts of globalization (new flows of labor, capital, commodities, and ideas) have promoted localized forest recovery.[41]

Another cause of deforestation is climate change. 23% of tree cover losses result from wildfires and climate change increase their frequency and power.[42] The rising temperatures cause massive wildfires especially in the Boreal forests. One possible effect is the change of the forest composition.[43]

In 2000 the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) found that "the role of population dynamics in a local setting may vary from decisive to negligible", and that deforestation can result from "a combination of population pressure and stagnating economic, social and technological conditions".[35]

The degradation of forest ecosystems has also been traced to economic incentives that make forest conversion appear more profitable than forest conservation.[44] Many important forest functions have no markets, and hence, no economic value that is readily apparent to the forests' owners or the communities that rely on forests for their well-being.[44] From the perspective of the developing world, the benefits of forest as carbon sinks or biodiversity reserves go primarily to richer developed nations and there is insufficient compensation for these services. Developing countries feel that some countries in the developed world, such as the United States of America, cut down their forests centuries ago and benefited economically from this deforestation, and that it is hypocritical to deny developing countries the same opportunities, i.e. that the poor should not have to bear the cost of preservation when the rich created the problem.[45]

Some commentators have noted a shift in the drivers of deforestation over the past 30 years.[46] Whereas deforestation was primarily driven by subsistence activities and government-sponsored development projects like transmigration in countries like Indonesia and colonization in Latin America, India, Java, and so on, during the late 19th century and the earlier half of the 20th century, by the 1990s the majority of deforestation was caused by industrial factors, including extractive industries, large-scale cattle ranching, and extensive agriculture.[47] Since 2001, commodity-driven deforestation, which is more likely to be permanent, has accounted for about a quarter of all forest disturbance, and this loss has been concentrated in South

When a Road Leads to Deforestation

After driving through the Congo rainforest for half a day, researcher Fritz Kleinschroth hopped out of the pick-up truck to find more than a dozen butterflies caught in the front radiator grille. The butterflies varied in orange, red, white, and blue, representing just a sliver of the diversity of insects and wildlife living in the Congo Basin. The driver of the logging truck was less focused on the butterflies and more enthusiastic about the drive through the rainforest. On this new dirt road, drivers could roll along at 120 kilometers (75 miles) per hour and reach previously remote areas.

To Kleinschroth, the memory from his 2017 visit to the Republic of Congo symbolizes the struggle in the rainforests of central Africa: how can people boost the local economy but minimize their footprint on the ecosystem? How can people build roads that bring in lucrative business without permanently destroying the habitats of the butterflies, chimpanzees, and elephants?

Finding this balance has become more urgent in recent decades, as more roads have been cutting across the Congo Basin, which spans six countries and contains the world’s second largest tropical forest. Roads often lead to more human activity and to unregulated or destructive events in the rainforest. They make it easier for people to move deeper into the rainforest for poaching, mining, or illegal logging.

In a new study, Kleinschroth and colleagues examined how road networks in the Congo Basin have changed over the past 15 years and how they have affected deforestation rates. The scientists showed that the total length of roads in the Congo Basin increased by 60 percent between 2003 and 2018. The rate of forest destruction caused by new roads has quadrupled since 2000.

However, the study also brought some positive news. The team found that not all roads lead to long-term deforestation. By closing logging roads when they are no longer in use, people can help avoid permanent damage to the forest—suggesting economic development and environmental conservation can co-exist.

“Road networks have grown a lot, but not every road is the same,” said Kleinschroth, lead author of the study and ecologist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zürich). “We can ensure that a road, if properly managed, does not necessarily need to lead to long-term deforestation.”

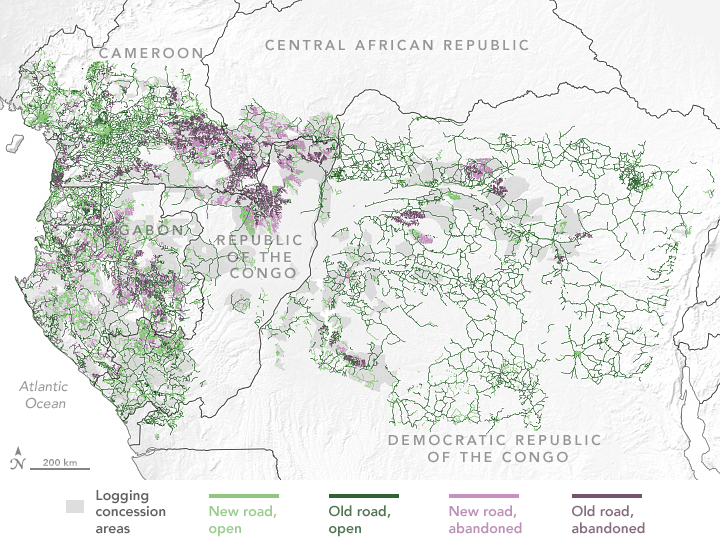

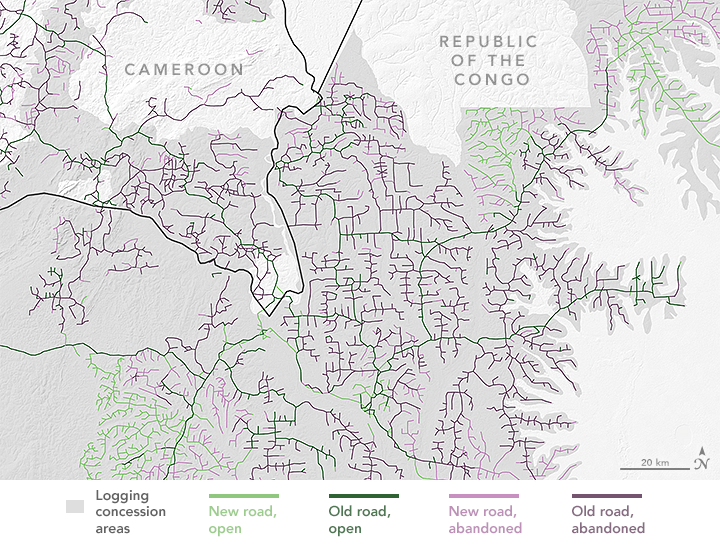

The maps on this page, based on data from Kleinschroth and colleagues, show the extensive road network across central African rainforests. Analyzing thousands of scenes from Landsat satellites, the team documented the three-decade evolution of roads across nearly two million square kilometers (1.2 million square miles). They classified the roads built before 2003 as “old” and those built after 2003 are labeled as “new.” Roads no longer in use are considered “abandoned,” and those still in use are “open.”

Some of the roads are tied to commercial logging, which has long been a main economic activity in the rainforest. Under long-term lease agreements (concessions) with local governments, private companies can move into a designated area of publicly-owned forest and harvest timber for a period usually lasting a few years. In this area, companies practice selective logging where only the most valuable tree species are cut, which usually results in cutting one tree per hectare on average. In order to harvest this timber though, the companies must build roads, usually unpaved, that allow the trucks to drive deep into the forest.

Other roads—usually outside of the logging concession areas—are aimed to improve public transportation networks. For instance, many roads are being built to complete the Trans-African Highway network, which aims to connect several countries with a paved highway. One of the last missing connectors in the network is a road that will connect the Republic of the Congo and the Central African Republic. This requires a new road, currently being built, that will be the first to directly cut through the Congo rainforest from north to south.

The researchers found that deforestation rates were highest within one kilometer of open old roads and outside of regulated logging concessions. Rates were higher, explained co-author and research professor at Northern Arizona University Nadine Laporte, because open roads help farmers establish small-scale agricultural plots, which are much more destructive to the land than selective logging activities. The Democratic Republic of Congo, where new logging concessions have been banned since 2002, has experienced the highest rates of deforestation due to agriculture and a high population density.

Deforestation rates over the study period were lowest around abandoned roads, where less human activity allowed forests to regrow over and around the unpaved roads. Most abandoned roads were located inside logging concessions. Because they are expensive to maintain, roads are often abandoned after a logging concession ends. In all, the team found that about 44 percent of roads inside logging concessions were abandoned by 2018 and no longer visible in satellite images.

“I was surprised at how many roads were abandoned and didn’t lead to additional deforestation,” said Scott Goetz, a co-author and professor at Northern Arizona University. “This is a positive result in the sense that our results show properly managed forest concessions can lead to less deforestation.”

The images above show a logging concession in a wetlands area of northern Congo. Both images were acquired by the Operational Land Imager on the Landsat 8 satellite on April 24, 2019; the natural color view (green background) uses bands 4-3-2, while the false-color (blue background) uses bands 7-6-5. False-color makes it easier for researchers to distinguish between vegetation and bare soil—and therefore easier to spot open, bare soil roads versus abandoned roads with vegetation growing over them.

“Building a new road into an intact forest is very problematic from a conservation point of view,” said Kleinschroth. “But for those roads that are closed after use, the impacts on the forest are much lower.”

Kleinschroth hopes that logging-concession holders—along with governments, local communities, and international funders—will more actively manage road projects. After all, he knows that certain roads are necessary for economic development. Like the driver of the pick-up truck from Kleinschroth’s field trip, many locals see new roads as business opportunities. But if local leaders promote closing temporary logging roads and lean into more sustainable activities, some of the Congo rainforest may remain intact for future generations.

amazing blog..................

ReplyDeleteNice brothekeep it up

ReplyDeleteNice work brother

ReplyDeleteNice 😁

ReplyDelete